Ever wonder how your four-year-old goes from giggling at silly rhymes to confidently sounding out words in their favorite bedtime story? The secret lies in something called phonological awareness, a fancy term for your child's ability to play with sounds in spoken language.

Sarah, a mom from Portland, discovered this firsthand when her preschooler Jake started noticing that "cat" and "hat" sounded similar during their evening nursery rhyme sessions. "I had no idea that his excitement about rhyming words was actually building the foundation for reading," she shared. "It felt like magic watching him connect those dots."

In this guide, you'll discover what phonological awareness really means, why it matters so much for your child's reading journey, and how you can support its development through simple, everyday activities that feel more like play than learning.

What Is Phonological Awareness?

Phonological awareness is your child's ability to recognize and play with sounds in spoken language before they even learn what letters look like. Think of it as developing a "good ear" for language. When your toddler claps along to the syllables in 'El-e-phant' or squeals with delight when you say 'Sir, Sir, Silly Snake', they're flexing their phonological awareness muscles.

This skill involves recognizing rhyming words, breaking words into syllables, recognizing when words start with the same sound, and ultimately isolating the individual sounds that form words. What makes this particularly important is that it all happens through listening and speaking, no worksheets or flashcards required.

This skill involves recognizing and producing rhyming words, breaking words into syllables and blending sounds together, identifying words that start with the same sound, and isolating individual sounds within words. What makes this particularly important is that it all happens through listening and speaking, no worksheets or flashcards required.

The research has consistently shown that phonological awareness is one of the most powerful predictors of reading success. Children who acquire these skills early tend to learn to read with greater ease and confidence.

Phonological Awareness vs. Phonemic Awareness vs. Phonics

Let's clear up the confusion around these three terms that sound remarkably similar but mean different things.

Phonological awareness is the big umbrella term. It includes working with syllables, rhymes, and the beginning and ending parts of words (called onset and rime). When your child recognizes that "moon" and "spoon" rhyme, or claps out the syllables in "but-ter-fly," they're demonstrating phonological awareness.

Phonemic awareness is the most specific skill under that umbrella, it's about hearing and manipulating individual sounds (phonemes) in words. When your child can tell you that "cat" has three sounds (/c/ /a/ /t/) or can change "cat" to "bat" by switching the first sound, they've developed phonemic awareness.

Phonics is different altogether because it involves letters and print. This is where children learn that the letter "b" represents the /b/ sound they've been hearing and playing with.

In the same way as learning music, phonological awareness involves recognizing all different sounds in music, including rhythm, melody, and beats. Phonemic awareness is the ability to hear individual notes in a song and swap them out to create different chords. Phonics is learning to read sheet music. To understand the written notation, it is necessary to hear and play with the sounds.

How Phonological Awareness Develops in Children

Children climb what experts call the "phonological awareness ladder," starting with big, easy-to-hear chunks of language and gradually working down to the smallest sounds. This progression feels natural to most children and follows a predictable pattern.

Words (Ages 3-4): Children first learn that sentences are made up of separate words, and that some words can be combined to make bigger words. They might enjoy compound word games like putting "cup" and "cake" together to make "cupcake."

Syllables (Ages 3-5): Next comes syllable awareness. Children love clapping or stomping to the beats in words like "di-no-saur" or "ham-bur-ger." This stage often coincides with their natural enjoyment of rhythm and music.

Onset and Rime (Ages 4-6): This involves breaking syllables into two parts: the onset (everything before the vowel) and the rime (the vowel and everything after). In the word "play," /pl/ is the onset and /ay/ is the rime. Children who can do this often excel at rhyming games and tongue twisters.

Phonemes (Ages 5-7): Finally, children develop the ability to hear and manipulate individual sounds. This is when they can tell you that "stop" has four sounds (/s/ /t/ /o/ /p/) or change "pig" to "big" by switching just the first sound.

Keep in mind that these age ranges are guidelines, not strict rules. It's perfectly normal for children to develop these skills either earlier or later. The key is to meet your child where they are and make the journey enjoyable.

Why Phonological Awareness Matters for Reading and Spelling

By understanding the significance of phonological awareness, you can appreciate the sound games your child plays with you. As literacy expert Wiley Blevins explains, "Phonemic awareness training provides the foundation on which phonics instruction is built. Thus, children need solid phonemic awareness training for phonics instruction to be effective."

When children can hear that "cat" has three distinct sounds, they're ready to understand that each sound can be represented by a letter. Without this foundation, phonics becomes a meaningless memorization exercise.

The connection to spelling is equally important. Children who can segment the word "frog" into /f/ /r/ /o/ /g/ can spell it by matching each sound to its corresponding letter. This makes spelling logical rather than a guessing game.

Did You Know? Children who struggle with phonological awareness often have difficulty with reading and spelling later on. But the good news is that early intervention can be a powerful way to develop these skills with support and practice.

Common Challenges and What to Watch For

While most children acquire phonological awareness naturally through exposure to language, songs, and wordplay, some may require additional assistance. These are indications that your child may need more practice:

● Difficulty recognizing or producing rhymes by age 4

● Trouble clapping along to syllables in familiar words by age 5

● Difficulty hearing when words start with the same sound by age 5

These challenges don't mean your child won't become a strong reader. Some children may just require more time and practice with these foundational skills before later excelling in reading. Children with dyslexia or auditory processing differences may require more explicit instruction, but with proper support, they can improve their abilities.

If you notice persistent difficulties, consider talking to your child's teacher or pediatrician. Early support can have a significant impact, and there are many effective ways to help children develop these skills.

Phonological Awareness Activities Parents Can Do at Home

The value of developing phonological awareness lies in its natural integration into everyday life. All you need is a willingness to play with language and no special materials or training. Here are some useful activities organized by skill level:

Rhyming and Word Play (Ages 3-5)

Nursery Rhyme Detective: Make familiar nursery rhymes interactive by pausing before rhyming words. "Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall, Humpty Dumpty had a great..." Let your child fill in "fall!" This builds anticipation and reinforces rhyming patterns.

Silly Rhyme Time: During car rides, create silly rhymes with your child's name or favorite things. "Jake the snake likes to bake a cake!" Children remember what makes them laugh, so the sillier the better. Encourage your child to join in and add their own rhymes. It’s okay if they make up nonsense words! The important thing is that they are practicing producing rhymes on their own.

Rhyming Riddles: Create simple riddles that end with rhyming words. "I'm thinking of something that rhymes with 'bat' and says 'meow.' What is it?" Start simple and gradually make them more challenging.

Syllable Games (Ages 4-6)

Syllable Hopscotch: Use chalk or tape to create boxes on the floor. Say a word and have your child hop into one box for each syllable they hear. "Elephant" gets three hops: "el-e-phant!"

Clap and Count: During dinner, clap out the syllables in family members' names or foods you're eating. "To-ma-to" gets three claps, "bread" gets one. Make it a game to see who can guess the number of syllables first.

Robot Talk: Speak like robots by saying words with exaggerated pauses between syllables. "I... love... choc-o-late!" Children find this hilarious and it reinforces syllable boundaries.

Onset-Rime Activities (Ages 4-6)

Same Beginning Sound Hunt: During grocery shopping, challenge your child to find items that start with the same sound as their name. A child named Colin might find a carrot, ketchup, and cookies. Remember that they are looking for the beginning sound (not letter), so the first letter of the items might be different from their name!

Sound Swapping: Start with simple words and change the beginning sound. "Let's change 'sun' to another word by switching the first sound! What happens if it starts with /f/ instead?" This prepares children for more advanced phoneme manipulation.

Phoneme Fun (Ages 5-7)

Sound Counting: Use small objects like blocks or buttons to represent each sound in short words. For "dog," place three blocks and touch each one while saying /d/ /o/ /g/.

Mystery Sound: Think of a three-sound word and give clues by saying the sounds separately. "/c/ /a/ /t/ - I'm furry and say meow!" Let your child blend the sounds to guess the word.

Sound Switch Games: Start with a word like "top" and systematically change one sound at a time: "top" becomes "hop" becomes "hip" becomes "hit." This advanced game builds flexibility with sounds.

The key to success is incorporating these activities into your daily routine rather than setting aside formal "lesson time." Practice when you are together: in a car ride, during their bath time, before bedtime.

Keep sessions short (5-10 minutes) and follow your child's lead. If they're excited and engaged, continue playing. If they seem tired or frustrated, try again later.

How to Know If Your Child Is on Track

Rather than formal testing, you can gauge your child's progress through everyday observations. Here's what to listen for:

Ages 2-4: Shows enjoyment of rhyming books, attempts to fill in rhyming words in familiar songs, notices when words sound similar.

Ages 4-5: Can clap syllables in their name and familiar words, recognizes obvious rhymes, enjoys alliteration and tongue twisters.

Ages 5-6: Can generate rhyming words independently, identifies beginning sounds in words, segments words into onset and rhyme.

Ages 5-7: Can count sounds in simple words, blends individual sounds into words, manipulates sounds to create new words.

Tips for Parents

The most effective way to teach phonological awareness is not at a desk with worksheets; it happens in the moments between moments, woven naturally into your family's daily rhythm.

Make it playful! The moment language play feels like work, children tune out. Keep activities light, fun, and pressure-free. If your child isn't in the mood for rhyming games, try again later.

Follow your child’s interests. If your child loves dinosaurs, play with the dinosaur alphabet! "Tyrannosaurus" has lots of syllables to clap!

Talk, talk, talk. Rich conversation is the foundation of all language skills. Narrate your day, ask open-ended questions, and really listen to your child's responses. The more language they hear, the stronger their phonological awareness becomes.

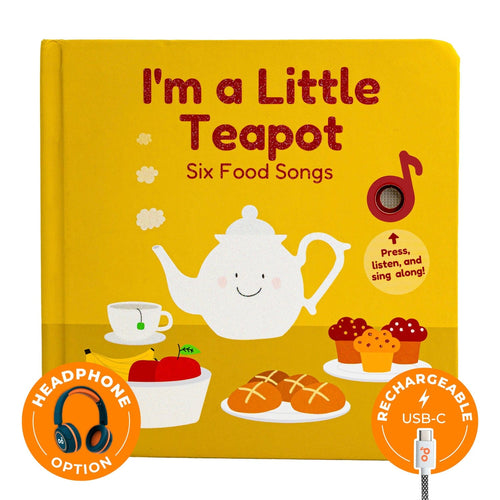

Use songs and books. Nursery rhymes, silly songs, and rhyming books naturally build phonological awareness. Don't underestimate the power of "Itsy Bitsy Spider" - such books are working harder than you might think.

Be patient with progress. Some children pick up these skills quickly, while others need more time and practice. Celebrate small victories and remember that building this foundation is an investment in your child's academic future and love of reading.

Consider helpful tools. Products like the infinibook can support phonological awareness development by allowing children to hear stories read aloud repeatedly, which builds familiarity with language patterns and sounds.

Keep it short and sweet! Frequent, brief practice sessions work better than long, intensive ones.

Maria, a kindergarten teacher and mother of two, puts it perfectly: "I used to think I needed a special curriculum to help my kids with reading. Then I realized that singing silly songs in the car and playing rhyming games during grocery shopping was doing more for their reading development than anything else."

The infinibook from Cali’s Books

We, at Cali's Books, have designed our sound books and the infinibook reader with phonological awareness development at the heart of the experience. Unlike traditional audio books that play straight through, children can replay their favorite rhyming sections, pause to predict what comes next, or focus on alliterative phrases that catch their attention.

The sound books have been chosen to have a lot of phonological elements, from simple rhyming patterns to more complex wordplay. When you use the recording capability to create personalized versions, your children can listen to how different voices handle challenging sound combinations.

Conclusion

It's a surprising fact that the human brain is not naturally wired to read. Speaking is a biological skill that develops naturally through human interaction, but reading requires explicit instruction and practice. Think again about how musicians train their ears before learning to read complex musical notation. The path your child takes towards reading is remarkably similar. Every time you play with rhymes, clap syllables, or let them listen to the same beloved story for the twentieth time, you're training their ear for written language.

The ancient Greeks understood a profound aspect of learning by making music and poetry inseparable from education. They were aware that all learning was based on rhythm, repetition, and sound patterns. When your toddler demands to hear the same story again and again, or when your preschooler drives you slightly crazy by repeating the same silly rhyme, they're doing the deep neurological work of building the pathways that will eventually make reading feel natural for them.